As should be apparent by now, my collection of hobby horses includes an interest in old translations of now-familiar texts.1 The interest is not entirely idiosyncratic, nor is it entirely irrelevant to my labors in that open-ended field known as the “intellectual and/or “conceptual history.” Exploring how earlier translators wrestled with terms that we now take for granted opens a window the way in which new concepts migrate from one language into another. That this process is hardly simple becomes clearest when the noise in translations becomes apparent.

Moses Mendelssohn’s answer to the question “What is enlightenment?” is a particularly interesting example. As I discussed in the previous post in this series, he maintained that difficulties in answering the question that had been posed in the Berlinische Monatschrift could be traced to the fact that (1) the word Aufklärung was of relatively recent vintage and (2) could only be understood in the context of two other important new-comers: Bildung and Kultur. When Dan Dahlstrom, Bert Kögler, and I were doing our translations of Mendelssohn’s essay in the 1990s, we had a luxury that our anonymous and neglected nineteenth-century predecessor lacked: well-established conventions for dealing with these terms. Our only problem was what to do with Bildung — a term that we could easily have rendered as “culture” were it not for the need to use that word to translate Kultur. In contrast, our predecessor was confronted by a semantic field consisting of finely drawn distinctions between terms that are just beginning to be rendered into English.

The German Museum and its “Proprietors”

Since the translation was published anonymously, there is no way of knowing whether the translator was (like Bert, but unlike Dan and me) a native German speaker, though given what we now know about the German Museum, I suspect that was likely. In the decade since I first worked on the German Museum, we have learned more about the editors of the journal and the broader context from which it emerged.2 In my article on the OED’s definition of “enlightenment,” I relied on Bayard Quincy Morgan and A. R. Hohfeld’s 1949 survey German Literature in British Magazine in crediting the editorship of the journal to “J. Beresford.”3 The current scholarship assigns editorial responsibility to Constantine Geisweiler, Peter Will, and Anton Willich.

Since the translation was published anonymously, there is no way of knowing whether the translator was (like Bert, but unlike Dan and me) a native German speaker, though given what we now know about the German Museum, I suspect that was likely. In the decade since I first worked on the German Museum, we have learned more about the editors of the journal and the broader context from which it emerged.2 In my article on the OED’s definition of “enlightenment,” I relied on Bayard Quincy Morgan and A. R. Hohfeld’s 1949 survey German Literature in British Magazine in crediting the editorship of the journal to “J. Beresford.”3 The current scholarship assigns editorial responsibility to Constantine Geisweiler, Peter Will, and Anton Willich.

There is a helpful discussion of the émigré bookseller and publisher Geisweiler (born Constantine de Giesworth) in a post on the Gothic Vault Facebook page. He seems to have arrived in London in the early 1790s and first enters the historical record when he married the German noblewoman Maria Countess Dowager of Schulenburg in 1799. Maria had already attained a measure of fame for her translations of various plays by August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue — who, at this point, was enjoying a measure of popularity in England (one of his plays turns up in Mansfield Park) — and the Geisweilers seem to have done their best to take advantage of the Kotzebue craze. But by 1806 Geisweiler had given up publishing and moved into the wine trade. Little is known about his later life except that Maria died in 1840 and, shortly afterwards, Constantine entered the Kensington House Lunatic Asylum, remaining there until his death in 1850.

Geisweiler had been aided in his publishing endeavors by Peter Will, an émigré clergyman who translated various Gothic novels into English (by now, it should be clear that we are dealing with interesting people). After the collapse of the German Museum, he left London for New York (where he was a minister to a German congregation) and then moved on to Curacao (preaching to a Dutch congregation). Eventually, he moved back to southern Hesse, where he established his own publishing house in 1839.

The philosopher Willich was best known of the three — both among his contemporaries and (thanks to Rene Wellek’s account of his role introducing Kant into England) to later scholars.4 Willich attended Kant’s lectures from 1778-1781 before setting off to Edinburgh where he studied medicine in the early 1790s and supported himself by offering German lessons — his students included Walter Scott. He moved to London in 1798 and gained employment (and, according to rumors, protection from creditors) by taking up the position of physician to the Saxon ambassador. In addition to his brief stint with the German Museum, he was also an editor for the Medical and Physical Journal. Finally, he too, jumped on the Kotzebue bandwagon with a translation of a biography of the playwright.

The editors of the German Museum (or, as they called themselves on those rare occasions when they found it necessary to speak collectively to their readers, the “Proprietors” of the journal) did little to identify themselves or their translators. Geisweiler was listed on the front page as the journal’s “printer.” Willich’s name appeared on the articles he wrote. And the initials “P.W.” — presumably the hard-working Peter Will — can be found at the end of quite a few of the translations.5 But all that appears at the close of the Mendelssohn translation is the letter X. Since I’ve not undertaken a systematic examination of the initials at the close of articles there is little point in trying to guess who might have done the translation. It may be enough to reflect on the challenges that X would have faced in attempting to put Mendelssohn into English.

Culture, Mental Illumination, and Civilization

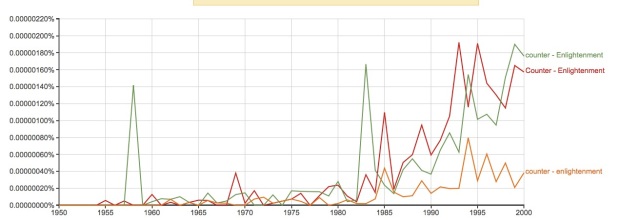

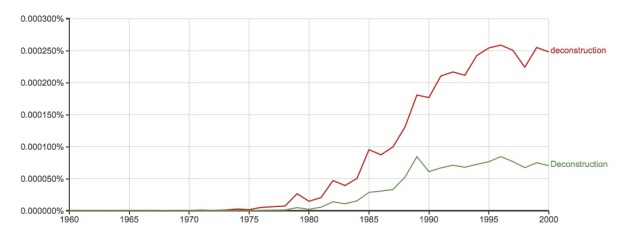

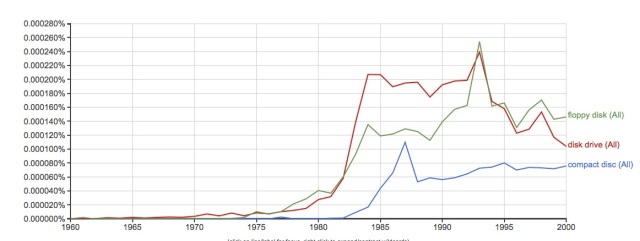

Then, as now, the easiest term to translate would have been Kultur — a French loan-word that appeared in Mendelssohn’s original draft as Cultur. A glance at an Ngram for the two spellings indicates that the French C was quite tenacious (can this possibly be correct?!). It is not until the start of the twentieth century that the Germanized spelling becomes consistently more frequent.

While Aufklärung would have presented greater problems in 1800, it is clear that the German Museum had a convention for translating it: “mental illumination.” A review of C. D. Vosz’s Das Jahrhundert der Aufklärung in the first volume referred to the book as “The Age of Mental Illumination” (I:435-436) and Georg Joachim Zollikofer’s “Der werth der grössern Aufklärung der Menschens” was translated as “An Estimation of the Advantages arising from the Program of Mental Illumination” (I: 396-403). A quick check of Volume II (the one volume that, to date, I have processed using OCR software) yields eight occurrences of the phrase “mental illumination” but none of “enlightenment” or “Enlightenment.”6 In contrast, “enlightening” used quite frequently (a total of twelve times, two of which occur in the text of the translation of the Mendelssohn essay). “To enlighten” occurs four times (“to enlighten the understanding of the multitude” (3), “to enlighten a whole nation by facts” (321), “a school to enlighten us” (343), and “endeavors to enlighten the nations” (477)). The translator strayed from the convention only slightly, preceding the words “enlightening the mind” with “intellectual improvement.”

Finally, confronted with problem of how to translate Bildung, the translator adopted a solution that never occurred to me (and, I suspect, would not have occurred to either Dan or Burt): civilization. That it wouldn’t have occurred to us has at least something to do what happened after 1800.

A Brief History of Bildung

Bildung is a word with a complicated history.7 It turns up quite frequently in Pietist theology, which — reviving elements from late medieval mystics such as Meister Eckhart and Heinrich Seuse who had presented Christ as the ideal “image” (Urbild) for a union of the human and the divine — used Bildung to denote the process by which individuals form themselves into the image of Christ through the performance of good works.8 It was also been used in the natural philosophy of Paracelsus, Böhme, and Leibniz to denote the development or “unfolding” of certain potentialities within an organism.9 In Klopstock, Wieland, Herder, and especially Goethe, it came to denote the ideal of an “aesthetic individualism,” in which individuals viewed the cultivation of their personalities into harmonious wholes as something comparable to the creation of a work of art — an ideal which could find support in Shaftesbury’s notion of a unity between the morally good and the aesthetically beautiful.10 For members of the educated middle class who came to positions in the bureaucracy and the clergy by virtue of their talents and education, Bildung served as a social ideal that stressed the virtue of individual self-cultivation over the accident of noble birth.11

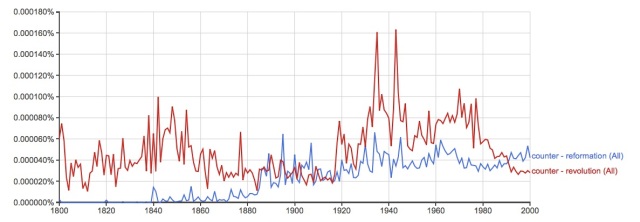

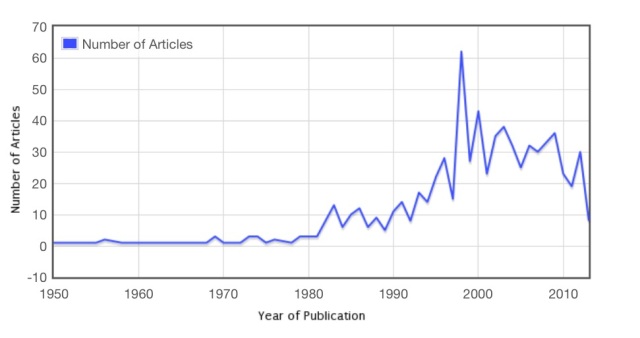

That Mendelssohn regarded Bildung — despite this rich and complicated history — as a new-comer might have had something to do with the publication, a decade earlier, of Herder’s Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte zur Bildung der Menschheit (1774). Ngrams for eighteenth-century texts are, of course, probably useless (if only because the sample of eighteenth-century that would have been sitting on library shelves when Google did its scanning can hardly have been representative of the corpus of texts published during the period) and the problems are even greater in the case of eighteenth-century German texts (e.g., what sorts of texts would North American and English libraries be collecting?). But it is, I suppose, of some interest that, among these alleged newcomers, Aufklärung seems to have been the last to catch on, with a slow ascent beginning in the middle of the 1760s and a sudden uptick around the time that Zöllner asked his famous question in the Berlinische Monatsschrift.

More revealing, perhaps, is the trajectory of the three terms over the century and a half between Zöllner’s question and the advent of National Socialism.

Bildung would seem to be the most successful of Mendelssohn’s three newcomers, with a rapid ascent during the two decades after his essay. Kultur exhibits a somewhat more modest climb, a sudden descent (as Bildung continues its rise), followed by a steady increase from 1860 onward. The lines for Bildung and Kultur join around the time of the cessation of hostilities in 1918. It would, of course, be necessary to spend some time poking around in the snippets to see what is taking place here, especially since a fair number of the occurrences of Bildung are likely to be the result of the emergence of pedagogy as a discipline and discussions of public education. But it bears remembering that Aufklärung, which consistently lags the other two terms also has close connections to pedagogical concerns.

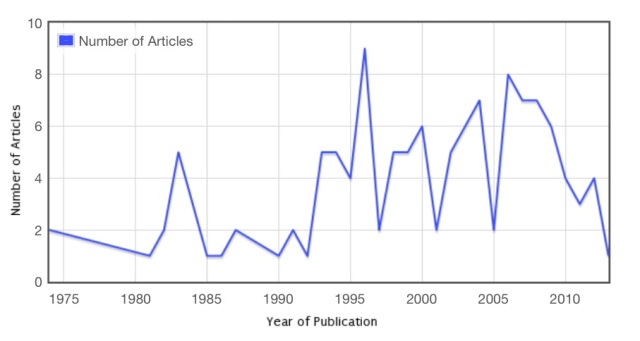

Substituting Erziehung for Kultur yields the following:

This Ngram, even more than is usually the case, leaves us with more questions than answers. Among the more important is the question of how many of the uses of Bildung and of Aufklärung over this period are simply discussions of education in the more specific sense that is typically associated with the term Erziehung? But that question, however important, is not the one that concerns me here. My interest lies with X’s decision to translate Bildung as “Civilization.”

Culture, Civilization, and the “Destiny of Man”

There were at least two reasons why it would have never occurred to me to translate Bildung as “Civilization.” The first has something to be said in its favor. The other is more problematic.

The best reason for avoiding “Civilization” is that it is out of sync with the religious resonances associated with Bildung. While “Education” doesn’t do much to convey these resonances either, it has the relative virtue of not ruling them out. Since at least Locke, English speakers have had the resources for differentiating the civil from the ecclesiastical and, employing these resources, have been able to argue that civil interests do not include the care of souls. Bildung, in contrast, has quite a bit to do with the care of souls and those of us who tend, almost instinctively, to think like John Stuart Mill (even if we haven’t read him) tend to think that the sort of care of souls that goes under the rubric of “cultivating individuality” is something that is best conducted beyond the reach of the state. And as those of us who have actually read On Liberty know, a good deal of what Mill was doing in the book rested on the account of Bildung that Wilhelm von Humboldt had provided.12

That X was likely unaware of these resonances is in keeping with his handling of what may well be the most crucial — and as well as the most underdeveloped — concept in Mendelssohn’s essay: that of the “Bestimmung des Menschen.” Dan and Bert, perhaps thinking of the famous essay by Fichte that carried the same title, rendered this as “vocation of man.” I considered that option, but went with “destiny of man,” in part because I wanted to capture the way in which the German Bestimmung allowed Mendelssohn to suggest that the definition of humanity lies in its destiny: it is what it becomes.

The term itself had been popularized by the clergyman Johann Joachim Spalding’s Bestimmung des Menschen (1748). Like Mendelssohn, Spalding was a member of the Berlin “Wednesday Society,” a secret society (known, privately, as the “Friends of Enlightenment) whose membership included the important figures in the Prussian bureaucracy, the Berlin clergy, and leading figures in Berlin intellectual life like Mendelssohn and Friedrich Nicolai.13 There is much to be said about Spalding’s book and, fortunately, Michael Printy has written a superb article on it, which appeared about a year ago in the Journal of the History of Ideas.14 Go read it (I’ll wait).

The term itself had been popularized by the clergyman Johann Joachim Spalding’s Bestimmung des Menschen (1748). Like Mendelssohn, Spalding was a member of the Berlin “Wednesday Society,” a secret society (known, privately, as the “Friends of Enlightenment) whose membership included the important figures in the Prussian bureaucracy, the Berlin clergy, and leading figures in Berlin intellectual life like Mendelssohn and Friedrich Nicolai.13 There is much to be said about Spalding’s book and, fortunately, Michael Printy has written a superb article on it, which appeared about a year ago in the Journal of the History of Ideas.14 Go read it (I’ll wait).

As Mendelssohn saw it, Bildung was composed of a theoretical side (which he termed “enlightenment”) and a practical side — “culture”). The goal towards which Bildung was oriented was defined by the Bestimmung des Menschen. It was the telos that the process of Bildung sought to attain and, in order to achieve that goal, it was necessary to bring the contrasting imperatives of Aufklärung and Kultur into harmony. Here is how I translated the paragraph where most of the work gets done (I must confess that I wince when I see Bildung translated as “education,” but — as I explained in the earlier post — it strikes me as the best of a set of bad options).

The more the social conditions of a people are brought, through art and industry, into harmony with the destiny of man, the more education this people has.

Education is composed of culture and enlightenment. Culture appears to be more oriented towards practical matters: (objectively) toward goodness, refinement, and beauty in the arts and social mores; (subjectively) towards facility, diligence, and dexterity in the arts, and inclinations, dispositions, and habits in social mores. The more these correspond in a people with the destiny of man, the more culture will be attributed to them, just as a piece of land is said to be more cultured and cultivated, the more it is brought, through the industry of men, to the state where it produces things that are useful to men. Enlightenment, in contrast, seems to be more related to theoretical matters: to (objective) rational knowledge and to (subjective) facility in rational reflection about matters of human life, according to their importance and influence on the destiny of man.

I posit, at all times, the destiny of man as the measure and goal of all our striving and efforts, as a point on which we must set our eyes, if we do not wish to lose our way.

Perhaps the most striking feature of X’s translation is that it doesn’t quite know what to do with Bestimmung des Menschen. X opted for “condition of man” as a translation, turning a term denoting a goal that must be achieved into a state that one has. This is coupled with a tendency to emphasize the political connotations associated with the term “civilization.” For example, the first paragraph of the passage quoted above was rendered (the complete translation can be found in an earlier post):

The more the state of society of any nation is made to harmonize through art and industry with the respective conditions of men, to so much greater degree of civilization has that nation attained.

What we have lost here is any sense that the goal that Bildung attempts to achieve transcends public life, a point that is essential if we are to understand the tensions that will later surface in Mendelssohn’s essay when he explores the way in which the destinies of “man as man” — that is, people as human beings — and “man as citizen” — human beings as members of political societies. The goal of Bildung is emphatically not simply to improve the “state of society of any nation” — it is to improve society. To understand the normative force of that word for eighteenth-century thinkers it might be worth recalling how Mendelssohn’s friend Lessing understood the true mission of the Masonic movement: to undo the divisions that civil society had introduced among human beings by bringing them together into a society that encompassed all.

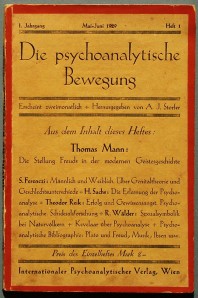

But while I think “civilization” doesn’t work as a translation for Bildung there is something about the choice that makes me reluctant to be too hard on X. This reluctance is bound up with my second, and less definable, reason why it would never have occurred to me to translate Bildung as “civilization.” Long before I knew about Spalding — indeed, long before I knew about Mendelssohn’s essay — I was already convinced that Bildung was a uniquely German word and “civilization” was, of course, French. Having read Thomas Mann, I knew that, in the run-up to the slaughter that began at the end of the summer of 1914, Kultur and Zivilisation had become opposing principles: Germans use the former, French use the latter, and the no-man’s land between them would be filled with rotting corpses.

While X’s choice of “civilization” as a translation for Bildung may have missed the particular nuances of Mendelssohn’s argument, there is something about it that gets to the heart of what Mendelssohn was attempting to do. The “Jewish Socrates” found a concept in the work of his Christian colleague that might be put to use in defining the tasks of enlightenment. That sort of bridging of divisions was also the goal of the Wednesday Society, whose rules forbad its members from calling each other by any titles they might hold and from talking about topics that were tied too closely to their vocations. The goal was to meet as human beings and talk about matters of common concern, a goal that — as Margaret Jacob puts it in her great study of the Masonic movement — amounted to attempting to live the enlightenment.

X’s search for an English word that might serve as a translation for the German Bildung was, in its own way, a small part of that same project. And so, of course, was the larger project of the German Museum: to enlighten English speakers about the efforts that German speakers were making to enlighten themselves. Even if the European Enlightenment had regional variations, it attempted to speak a common language, a language that might permit people from different nations to become members of that cosmopolitan community of readers and writers that would be sketched in that other famous answer to Zöllner’s question. Measured against that effort, perhaps X’s difficulties with Bildung hardly matter.

- The earliest public manifestation of this interest was a somewhat idiosyncratic article that was a great deal of fun to write: “A Raven with a Halo: The Translation of Aristotle’s Politics,” History of Political Thought, VII:2, (1986) 295-319 ↩

- For what follows, I am indebted to two articles by Barry Murnane, “Radical Translations: Dubious Anglo-German Cultural Transfers in the 1790s,” in (Re-) Writing the Radical: Enlightenment, Revolution and Cultural Transfer in 1790s Germany, Britain and France, ed. Maike Oergel, Spectrum Literaturwissenschaft/spectrum Literature 32 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), 44–60 and “Gothic Translation: Germany, 1760-1830,” in The Gothic World, ed. Glennis Byron and Dale Townshend, Routledge Worlds (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), 231–42 and to the discussion in John R. Davis, The Victorians and Germany (Lang 2007) 54. There is a passing discussion of the German Museum and of Peter Will on p. 62 of Rudolf Muhs’ article “Geisteswehen: Rahmenbedingungen Des Deutsch-Britischen Kulturaustauschs Im 19. Jahrhundert” in R. Murhs, J. Paulmann, W. Steinmetz, eds. Aneignung und Abwehr. Interkultureller Transfer zwischen Deutschland und Grossbritannien im 19. Jahrhundert (Bodenheim, 1998) 44-70. ↩

- Bayard Quincy Morgan and A. R. Hohlfeld, editors, German Literature in British Magazines 1750-1860 (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1949) 47-49. ↩

- René Wellek, Immanuel Kant in England 1793-1838 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1931) 11-15. There are passing citations of the German Museum on 15 and 18, the fruits, presumably, of Wellek’s encounter with the copy in the Houghton Library that I would read some seven decades later. ↩

- In Volume II (currently the only volume that I’ve run OCR software on), there are at least ten articles credited to “P. W.” (while the text is clean enough to yield a fairly good OCR layer, I doubt it catches everything). In contrast, two very short pieces are signed “M. G.” (presumably Maria Geisweiler, the married name of Countess Maria von Schulenburg, though there is also one M. S., which could conceivably also be by her). None are signed A. W. or C. G. ↩

- I’m in process of converting the other two volumes and would be happy to share the finished products (to the extent that Google’s copyright claims permit) with anyone who would be interested in working with them (what is currently available on Google consists of image files only). ↩

- The standard discussions include Rudolf Vierhaus, “Bildung” in O. Brunner, W. Conze, R. Koselleck (eds.), Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe I, 508-551, Hans Weil, Die Entstehung des deutschen Bildungsprinzip (Bonn: Bouvier, 1930), and W. H. Bruford, The German Tradition of Self-Cultivation: ‘Bildung’ from Humboldt to Thomas Mann (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975).

↩ - See E.L. Stahl, Die Religiose und die Humanitätsphilosophische Bildungsidee (Bern, 1934), 97-101 and Hans Sperber, “Der Einfluss des Pietismus auf die Sprache des 18 Jahrhunderts,” Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, VIII (1930), 508-9. ↩

- Vierhaus, 510 ↩

- See David Sorkin’s wide-ranging discussion in “Wilhelm Von Humboldt: The Theory and Practice of Self-Formation (Bildung), 1791-1810,” Journal of the History of Ideas 44:1 ( 1983): 55-73 and his shorter account in The Transformation of German Jewry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987) 16-7. ↩

- Hans Rosenberg, Bureaucracy, Aristocracy, and Autocracy 182-6 and Fritz K. Ringer, The Decline of the German Mandarins (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969) 8-12, 15-25, 86-90. For a discussion of the transformation of the concept within German neo-humanism in the two decades after Mendelssohn’s essay, see Anthony J. La Vopa, Grace, Talent, and Merit 264-78 ↩

- What we (or, at least what I) don’t know is how much of Mill’s acquaintance with German philosophy may have had something to do with his contact with Sarah Austin, the sister of Harriet Taylor (the object of Mill’s affections) and the wife of John Austin (the great English jurist). I’ve said a few things about her in an earlier post, but someone should spend more time working on this interesting woman. ↩

- I’ve written about them in a variety of places, including the introduction to my collection What is Enlightenment?. ↩

- Michael Printy, “The Determination of Man: Johann Joachim Spalding and the Protestant Enlightenment,” Journal of the History of Ideas 74:2 (2013): 189–212. ↩