Last Sunday (which, for those of us who live in the Boston area, seems like the distant past), I began an examination of Karl Popper’s comments on Isaiah Berlin’s 1958 lecture “Two Concepts of Liberty” in his letter to Berlin of February 17, 1959. Popper’s letter struck me as worth discussing for two reasons. First, Berlin’s Two Concepts is interesting in its own right: it is an influential — though at times quite puzzling — discussion of a central political concept and Popper’s letter allows us to see how one of Berlin’s contemporaries tried to make sense of its arguments. Second, the discussion between Berlin and Popper sheds some light on the diverging ways in which two self-described liberals, at the height of the Cold War, thought about the Enlightenment and its implications. In this post, I’ll finish the discussion of Popper’s letter by considering the second of the two points he raised. Next week, I’ll finish off the discussion by examining Berlin’s response.

A Kantian Case for Positive Liberty

Popper’s second point consists of a proposal and a question. The proposal takes the form of an alternative way of thinking about “positive” liberty. The question has to do with what strikes Popper as Berlin’s antipathy towards Horace’s phrase “sapere aude.” Our first task will be to figure out how the proposal (which is, I think, straightforward enough) is related to the question (which is, at first glance, a bit obscure).

Here is the relevant section of Popper’s letter (which consistently renders “sapere aude” as “sapere ande” — an error I have not transcribed here — and includes a minor typo that I’ve crossed out):

My second point is your picture of positive freedom. It is a marvelous elaboration of the idea of being one’s own master. But is there not a very different and very simple idea of positive freedom which may be complementary to negative freedom, and which does not need to clash with it? I mean, very simply, the idea to spend one’s own life as well as one can; experimenting, trying to realize in one’s own way, and with full respect to others (and their different valuations) what one values most? And may not be the search for truth — sapere aude — be part of a positive idea of self-liberation? What have you against sapere aude? No doubt, the idea that anybody is wise, is dangerous and repugnant. But why should sapere aude be interpreted as authoritarian? It is, I feel, anti-authoritarian. When Socrates said, in the Apology, that the search for truth through critical discussion was a way of life (in fact, the best way of life he knew of) — was there anything objectionable in this?

The connection that Popper seeks to draw here between the “very different and very simple” example of “positive freedom” that he offers and his defense of the “anti-authoritarian” implications of Horace’s sapere aude becomes somewhat clearer if we look at the lecture Popper had given (five years before Berlin delivered his inaugural lecture) on the BBC to mark the sesquicentennial of Immanuel Kant’s death.

Popper began his homage to Kant by recalling the unexpectedly large crowds that gathered for the great philosopher’s funeral:

They came to show their gratitude to a teacher of the Rights of Man, of equality before the law, of world citizenship, of peace on earth, and, perhaps most important, of emancipation through knowledge (175).

Popper’s invocation of the idea of “emancipation through knowledge” sets the stage for a brief discussion of Kant’s response to the question “What is Enlightenment?” and a consideration of Kant’s role as the “last great defender” of the Enlightenment. After quoting the opening paragraph of Kant’s answer, which culminates in Horace’s sapere aude, Popper provided the follow explanation:

Kant is saying something very personal here. It is part of his own history. Brought up in near poverty, in the narrow outlook of Pietism … his own life is a story of emancipation through knowledge. In later years he used to look back with horror to what he called “the slavery of childhood,” his period of tutelage. One might well say that the dominant theme of his whole life was the struggle for spiritual freedom.

With those last four words we arrive at the nub of Popper’s second comment on the Two Concepts. How can we to situate Kant’s “struggle for spiritual freedom” within Berlin’s distinction between “positive” and “negative” forms of liberty?

What is at stake in this struggle is not a question of the extent of the space in which an individual “is or should be left to do or be what he wants to do or be, without interference by other persons” (i.e., “negative” liberty). I can be “negatively” free to engage in any number of activities that I am “spiritually unfree” (e.g., because of fear or ignorance) to undertake. Kant characterizes enlightenment in terms of an escape from a state of “self-incurred tutelage [Unmündigkeit]” — a condition for which I am myself responsible. So the question of whether I am free or not turns on whether I am or am not exercising “mature autonomy” (one of a variety of terms that translators have used to try to capture the implications of the German Mündigkeit). What is involved, then, in the pursuit of enlightenment turns on considerations that were nicely captured by Berlin in his initial definition of “positive” liberty: “What, or who, is the source of control or interference, that can determine someone to do, or be, one thing rather than another?” Kant’s subsequent account of the differences between “public” and “private” uses of reason can, without too much difficulty, be understood as involving questions about the extent to which subjects are free, or not free, to articulate certain positions — i.e., with what Berlin characterizes as the “negative” concept of liberty. But Popper is not concerned with that discussion. What interests him, instead, are the broader implications of the motto that Kant took from Horace, a motto that Popper sees as summarizing the story of Kant’s life: “a story of emancipation through knowledge.” And this, of course, is a question about “positive,” rather than “negative,” liberty.

Berlin’s Case Against Positive Liberty

It would have been hard for Popper to overlook the degree to which Berlin’s critique of the concept of “positive” liberty represents a critique of the very idea that he had praised in his own discussion of Kant. Section IV of the Two Concepts lecture closed with a full-throated attack on what Berlin characterized as “the positive doctrine of liberation by reason,” which argued that,

Socialized forms of it, widely disparate and opposed to each other as they are, are at the heart of many of the nationalist, communist, authoritarian, and totalitarian creeds of our day. It may, in the course of its evolution, have wandered far from its rationalist moorings. Nevertheless, it is this freedom that, in democracies and in dictatorships, is argued about, and fought for, in many parts of the earth today.

Several pages later, in the sprawling second paragraph of Section V, he resumed his attack on the idea of “liberation through reason” by noting how it had figured in the work of such otherwise different thinkers as Spinoza, Locke, Montesquieu, Kant, and Burke and then went on to conclude,

The common assumption of these thinkers (and of many a schoolman before them and Jacobin and Communist after them) is that the rational ends of our ‘true’ natures must coincide, or be made to coincide, however violently our poor, ignorant, desire-ridden, passionate, empirical selves may cry out against this process. Freedom is not freedom to do what is irrational, or stupid, or wrong. To force empirical selves into the right pattern is no tyranny, but liberation.

But the passage in Berlin’s lecture that appears to have most concerned Popper was the opening paragraph of Section IV, where Berlin states that, when “free self-development” becomes the standard for determining whether one is truly free, individuals tend to view the various “obstacles which present themselves as so many lumps of external stuff” blocking the achievement of this goal. He continues,

That is the programme of enlightened rationalism from Spinoza to the latest (at times unconscious) disciples of Hegel. Sapere aude. What you know, that of which you understand the necessity — the rational necessity — you cannot, while remaining rational, want to he otherwise. For to want something to be other than what it must be is, given the premisses — the necessities that govern the world — to be pro tanto either ignorant or irrational. Passions, prejudices, fears, neuroses, spring from ignorance, and take the form of myths and illusions. To be ruled by myths, whether they spring from the vivid imaginations of unscrupulous charlatans who deceive us in order to exploit us, or from psychological or sociological causes, is a form of heteronomy, of being dominated by outside factors in a direction not necessarily willed by the agent. The scientific determinists of the eighteenth century supposed that the study of the sciences of nature, and the creation of sciences of society upon the same model, would make the operation of such causes transparently clear, and thus enable individuals to recognize their own part in the working of a rational world, frustrating only when misunderstood. Knowledge liberates by automatically eliminating irrational fears and desires.

There is more to say about what Berlin seems to be doing in this paragraph, but for now it may be enough to suggest that his use of the motto from Horace that had served as the touchstone for Popper’s encomium to Kant clarifies the context for the question that Popper posed to Berlin in his “second point”: “What have you against sapere aude”?

Histories, Individual and Collective

Popper had good reason to be puzzled by the link Berlin sought to establish between the “positive” conception of liberty and totalitarian forms of domination: the Two Concepts lecture was not entirely clear as to how this relationship was to be understood.

At the beginning of the discussion of “The Notion of Positive Liberty” (Section II of the lecture), Berlin explained that his intent was to show how the two concepts of liberty, which might initially seem to have been nothing more than two perspectives on the basic idea, had “diverged” over time. Here’s how he presents this in second paragraph of Section II:

The freedom which consists in being one’s own master, and the freedom which consists in not being prevented from choosing as I do by other men, may, on the face of it, seem concepts at no great logical distance from each other — no more than negative and positive ways of saying much the same thing. Yet the ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ notions of freedom historically developed in divergent directions until in the end, they came into direct conflict with each other.

This suggestion that, while the “logical distance” between positive and negative conceptions of liberty may not be that great, their historical development proved to be quite different, would seem to be setting the stage for an historical account of how this divergence came about. But the lecture never quite provides one.

What Berlin offers, instead, is a condensed (albeit quite evocative) sketch of “the independent momentum which the metaphor of self-mastery acquired.” This sketch is notable for what it doesn’t contain: anything approaching an account of an historical transformation of a concept. Berlin starts with a passing reference to T. H. Green and then goes on to trace the “momentum” of the concept of self-mastery. Let’s look at the passage in question and then try to make sense of what is going on:

Have not men had the experience of liberating themselves from spiritual slavery, or slavery to nature, and do they not in the course of it become aware, on the one hand, of a self which dominates, and, on the other, of something in them which is brought to heel? This dominant self is then variously identified with reason, with my ‘higher nature’, with the self which calculates and aims at what will satisfy it in the long run, with my ‘real’, or ‘ideal’, or ‘autonomous’ self or with my self ‘at its best’; which is then contrasted with irrational impulse, uncontrolled desires, my ‘lower’ nature, the pursuit of immediate pleasures, my ’empirical’ or ‘heteronomous’ self, swept by every gust of desire and passion, needing to be rigidly disciplined if it is ever to rise to the full height of its ‘real’ nature. Presently the two selves may be represented as divided by an even larger gap: the real self may be conceived as something wider than the individual (as the term is normally understood), as a social ‘whole’ of which the individual is an element or aspect: a tribe, a race, a church, a state, the great society of the living and the dead and the yet unborn. This entity is then identified as being the ‘true’ self which, by imposing its collective, or ‘organic’, single will upon its recalcitrant ‘members’, achieves its own, and therefore their, ‘higher’ freedom. The perils of using organic metaphors to justify the coercion of some men by others in order to raise them to a ‘higher’ level of freedom have often been pointed out. But what gives such plausibility as it has to this kind of language is that we recognize that it is possible, and at times justifiable, to coerce men in the name of some goal (let us say, justice or public health) which they would, if they were more enlightened, themselves pursue, but do not, because they are blind or ignorant or corrupt. This renders it easy for me to conceive of myself as coercing others for their own sake, in their, not my, true interest.

What we seem to have here is a discussion of the dangers associated with the use of a metaphor: the metaphor of “self-mastery.” These dangers are illustrated by tracing a path that leads from an experience of liberation to a new form of slavery. To simplify (without, I hope, distorting Berlin’s argument ), the steps in the path might be summarized as follows:

- An experience of liberation from some form of “slavery”

- A subsequent interpretation of this experience in terms of a contrast between between two different “selves”

- The identification of one of these selves with a larger collectivity

- The exercising of coercion over the self that is not identified with the collectivity.

These steps are sufficiently abstract to allow them to be interpreted in a variety of ways. We might, for example, think of them as stages in the development of an individual. For example:

- After a youth spent in various pursuits, a young man experiences, for the first time, a sense of purpose and coherence in his life

- He identifies this new sense of coherence and purpose with the “new” (“truer” and “purer”) person he has become, a person that has overcome the temptations that dogged the “old” person that he was

- He finds a larger community (religious or political) that offers him a language in which he can articulate this experience, a language that carries on the interpretation that he has begun at step 2 by linking it to this larger community (e.g., as the distinction between those who have been “enlightened” vs those who remain in the “darkness”).

- As a member of this community the young man engages in aggressive efforts at recruitment and “conversion” (perhaps at the behest of his superiors) of others, in order to bring others (who remain in the darkness from which he has escaped) into “the light.”

While a narrative of this sort may have a certain plausibility — especially for those of us who spent Friday “sheltering in place” and watching more television than anyone should — we can, just as easily, imagine more benign versions. For example:

- a recent college graduate, having double majored in Economics and English, weighs the decision of whether to accept a promotion in the financial firm at which she is employed, but recognizes that accepting this position will mean increased demands on her time that will require her to abandon the writing she has been doing in her spare time. She concludes that the time has come to quit her job (which she finds rather tedious) and instead to pursue a career as a writer.

- Upon making this decision, she experiences a certain relief — indeed a “liberation” — in the realization that, all along, she had “really” been “a writer”, rather than an aspiring investment banker (this recognition may also help her to understand why she found work at the firm so tedious).

- She joins a group of writers in her city who get together from time to time to discuss their work and provide support to each other.

- The group she has joined also includes individuals who have yet to quit their day jobs and are, indeed, wrestling with the sort of decision that our recent college graduate has already made. She discusses the challenges and rewards of the path she has taken with those who are still trying to figure out what they should be doing.

Both of these narratives — and any number of other stories of this sort that we might want to construct — consist of a sequence of moves that, for all their apparent logic, are beset by any number of contingencies. The transition from step 1 to 2 may perhaps seem slightly less contingent than the other steps because we are familiar with the set of metaphors that both individuals are using to interpret their experience. But the interpretation of the experiences undergone at step 1 in terms of the metaphor employed in step 2 rests on the fact that the individuals in these stories being members of communities in which these sorts of metaphors have some currency. And, pushing on through the remainder of the steps, it is less than obvious that metaphors of this sort possess any sort of “independent momentum” that requires the individual who, at step 2, takes up the metaphor of “self-mastery,” to march onward through steps 3 and 4. Obviously, not all individuals who experience religious conversions wind up packing shrapnel into pressure cookers and not all accountants turned writers become members of writer support groups.

But while it may be appealing to read Berlin’s steps as describing a sort of personal history of the sort that I have constructed (at least it appeals to me, since it makes some sense of the process that he seems to be tracing), Berlin had something else in mind. He was attempting to trace the trajectory of an idea, not a life, which means that movement from step 1 through step 4 has to be reformulated as a sort of “biography of an idea” — i.e., as a history of the concept of “freedom,” cast in the form of a “history of ideas” written in the Great Books style: ideas are passed from thinker to thinker and reformulated along the way. But, while this sort of history lies at the heart of the transition that Berlin sketched at the start of Section II, this isn’t what he proceeds to offer in the remainder of the Two Concepts lecture. What we find instead is something that looks, at best, like an account of the implications of a metaphor and, at worst, like the “movement of the Concept.”

Berlin’s “Phenomenology of Freedom”: Self-Mastery, Self-Abnegation, and Self-Realization

So, let’s try again, this time talking about the history of a concept rather than the biography of an individual. Berlin’s account of the vicissitudes of the concept of “positive liberty” goes as follows.

- He begins with a brief discussion, in Section II, of the “desire to be self-directed” and then proceeds, in the next two sections, to explore the two directions that efforts to achieve such self-direction have taken.

- Section III (“The Retreat to the Inner Citadel”) considers the project of “self-abnegation,” i.e., the attempt to “strive for nothing that I cannot be sure to obtain.”

- Section IV (“Self-Realization”) focuses on a strategy of liberation that he sees as central to the project of “enlightened rationalism”: this project involves understanding what “rational necessity” demands and making this necessity into one’s own project.

- Finally, Section V (“The Temple of Sarasto”) examines how adepts at the project outlined in Section IV impose such projects on others in order to lead them (or, more bluntly, to force them) to “true” freedom.

These sections can, without too much difficulty, be mapped onto steps 2 through 4 of the sequence that I constructed above. Section III of the lecture generates a division between “rational” and “irrational” selves of the sort that can be found at step 2 of my earlier reconstruction. Section IV — with some difficulty (which can be clarified in a moment) — can be seen as a sort of merging of the “rational self” into a larger collectivity (e.g., one of Berlin’s favorite examples for this is a musician learning to play a composition and, in doing so, becoming “free” by subjecting himself or herself to the score). And Sarastro’s “enlightened despotism” in Section V is, quite transparently, an example of what Berlin sees at work in step 4.

As we make our way through these three sections we encounter many proper names (Kant, Spinoza, Montesquieu, Burke, Hegel etc.), but it is hard to get a grasp on how these names are supposed to be arranged into anything like a history of ideas (even in the Great Books style). While Berlin (like Popper) disliked Hegel intensely, the experience of reading these sections is not unlike the confusion that begins to settle over a reader of Hegel’s Phenomenology: concepts are on the move, changing their implications as they make their progress; glimpses of the development of these concepts can be seen in this or that thinker (though Hegel, unlike Berlin, is sparing in his use of proper names), but it is not always obvious how the discussion is supposed to line up with anything that resembles an actual history.

Kant’s name turns up quite a bit in Section III, where he serves as an illustration of how the breach between the “two selves” comes about. In Berlin’s account, the “retreat to the inner citadel” rests on the separating off of a “‘noumenal’ self” that remains free, even though the phenomenal self may be subject to external forces.

From this doctrine, as it applies to individuals, it is no very great distance to the conceptions of those who, like Kant, identify freedom not indeed with the elimination of desires, but with resistance to them, and control over them. I identify myself with the controller and escape the slavery of the controlled. I am free because, and in so far as, I am autonomous. I obey laws, but I have imposed them on, or found them in, my own uncoerced self. Freedom is obedience, but ‘obedience to a law which we prescribe to ourselves’ and no man can enslave himself.

From time to time, we find discussions in the Two Concepts lecture that provide something approximating an account of the development of metaphors and their appropriation by historical actors. For example, four paragraphs from the end of Section III, Berlin observes:

Kant’s free individual is a transcendent being, beyond the realm of natural causality. But in its empirical forms — in which the notion of man is that of ordinary life — this doctrine was the heart of liberal humanism, both moral and political, that was deeply influenced both by Kant and by Rousseau in the eighteenth century. In its a priori version, it is a form of secularized Protestant individualism, in which the place of God is taken by the conception of the rational life, and the place of the individual soul which strives towards union with Him is replaced by the conception of an individual, endowed with reason, straining to be governed by reason and reason alone and to depend upon nothing that might deflect or delude him by engaging his irrational nature. Autonomy, not heteronomy: act and not to be acted upon. The notion of slavery to the passions is — for those who think in these terms — more than a metaphor.

What Berlin might be suggesting here is that Kant provides a secularized form of Protestant theology and that — perhaps because his discussion of autonomy and heteronomy shared much with a more culturally pervasive appropriation of religious accounts of divisions within the soul — his particular way of framing these discussions went on to have a broad appeal to “liberal humanists” (e.g., liberals who were looking for non-religious ways of reframing the religious traditions from which they were coming?). An account of this sort might help clarify why the metaphor of self-mastery could take on a “momentum” that would allow it to complete the passage from step 1 to step 4. But it is hard to see how Berlin can characterize this “momentum” as in any sense “independent.” There is no logical explanation for the transition from step 1 to step 4 nor is it clear that the metaphor of “self-mastery” has any inherent relationship to the later discussions of “self-realization” or self-enslavement. If there is a connection here, it is an historical or cultural one. At the close of Section IV, Berlin is content to note that, in the account he has been offering, the idea of positive liberty has, “wandered far from its rationalist moorings.” Explaining that it is not his intent “to trace the historical evolution [emphasis mine] of this idea,” he proposes instead “to comment on some of its vicissitudes.” And, with that, we move on to the discussion of Sarastro’s Temple.

A Brief Consideration of the Flexner Lectures

Berlin had, however, attempted an account of the “historical evolution” of the idea of positive liberty some six years earlier as part of his Flexner Lectures at Bryn Mawr College. An adequate discussion of these lectures would drag this already lengthy set of posts out to an intolerable length. And, in any case, it would be folly for me to attempt such an account without having had the chance to read Joshua Cherniss’s recently published discussion of the development of Berlin’s thought, which draws on archival materials that I have not examined.But, at the risk of having Cherniss’ book prove me wrong (and I’m enough of a Popperian not to get worked up about being proven wrong), here is my take on what is going on in the Flexner Lectures.

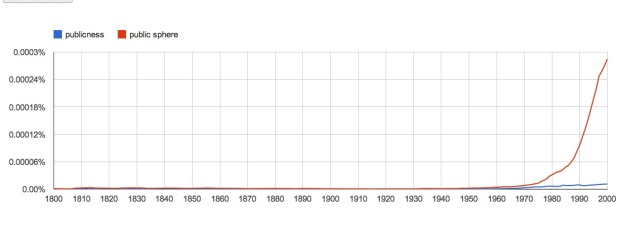

The history of ideas that Berlin offered at Bryn Mawr began by tracing the way in various Enlightenment thinkers (among them, Helvetius) advanced a concept of liberty that is grounded on the accumulation of natural scientific knowledge of the functioning of the world. This knowledge was seen as potentially liberating in two ways. In the case of the various illusions and prejudices that held sway over the human mind, a demonstration of their falsity was sufficient to break their hold. Further, human liberty could also be enhanced by an understanding of the actual constraints that nature places on human actions. In this case, emancipation took the form of the development of strategies that echoed Bacon’s idea that, in order to command nature, we must first learn how to obey her. It is important, I think, that there is no talk at this point about a division between “true” and “false” selves nor any suggestion that knowing how nature operates necessarily requires the leap that Berlin makes at the start of Section IV of the Two Concepts lecture when sapere aude is identified with a process in which individuals achieve liberty by subjecting their own ends to those of nature. Pangloss may do this, but Candide winds up learning that work (or, as Habermas would have it, “purposive-rational action”) is a reasonable alternative. And Voltaire, as we know, didn’t try to convince himself that torturing Huguenots was part of the “rational necessity” of the world.

In the Flexner Lectures, the discussion of these (“Enlightenment”) strategies for advancing human liberty is followed by an analysis of what he terms the “romantic conception” of liberty. As would be the case in the Two Concepts lecture, Kant’s role in this story lies in his distinction between two different “selves” (noumenal and phenomenal) (see pp. 147–148 and 173), which serves as the premise for Berlin’s discussion of the notion of “positive freedom” (166). The narrative that Berlin offered at Bryn Mawr associates “positive freedom” with what he terms the “romantic” rather than the “liberal” conception of liberty, and much of his discussion of it is accomplished in an extended account of Fichte (177–198). In Fichte, Berlin found a thinker who might be seen as tailor-made for demonstrating the dangerous “momentum” of the concept of “self-mastery”: the Wissenschaftslehre corresponds to the distinction between the “free” self and the “subject” one (step 2 in the sketch above), while The Addresses to the German Nation show how such a distinction might be transferred to a collectivity (step 3 above). But since Fichte is, in Berlin’s eyes, a “romantic” not an Aufklärer, a considerable reshuffling of labels is necessary in order to produce the account offered in the Two Concepts.

The label “romantic liberty” was jettisoned and the roots of “positive liberty” were seen as reaching back to (at least) the Enlightenment. This shift allowed Berlin, in the lectures, articles, and drafts that would follow in the wake of the Two Concepts, to bring the Romantics, along with that odd assortment of thinkers who make up the Counter-Enlightenment, onto the field as the opponents of what, in the Flexner lectures, had been characterized as the “Romantic conception” of liberty. It is possible that this may, in part, have provided a reason for avoiding an historical account of the transformation of the concept in the Two Lectures. Not only would it have been difficult to work such a discussion into the limited space permitted in his inaugural lecture, but it is also possible that Berlin was not, at least at this point, entirely settled on how such a history might be presented.

Popper on Positive Liberty as Self-Legislation

Had Popper been familiar with how Berlin’s argument had been developed in the Flexner Lectures, it would have done little to remove his reservations about Berlin’s attitude towards Horace’s “sapere aude.” Though Fichte might have shown how a thinker could run through the steps that culminated in subjection to the authority of the ”enlightened“ that had been previewed in the third paragraph of Section II and ultimately cashed out in the discussion of Saratro’s Temple in Section V, Popper would have had considerable difficulties in seeing Fichte as a legitimate heir of Kant. He had emphatically rejected that line of interpretation in his BBC lecture:

Kant believed in the Enlightenment. He was its last great defender. I realize that this is not the usual view. While I see Kant as the defender of the Enlightenment, he is more often taken as the founder of the school which destroyed it — of the Romantic School of Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel. I contend that these two interpretations are incompatible.

What separates Berlin and Popper, then, are two rather different accounts of the relationship between “the Enlightenment” and “the Romantics.” These interpretations, to be sure, are creatures of a period in which the lines between enlightenment, idealism, and romanticism tended to be drawn more starkly than we might be inclined to draw them today. This difference in how Berlin and Popper situate Kant leaves us with two self-described liberals — both wary of the threat posed by a totalitarian enemy — who offer markedly diverging accounts as to how to trace the history of the ideas that laid the foundations for the enemy they both oppose.

But since the Two Concepts offered rather little of this history of ideas, their disagreement may not have been quite as significant for Popper as it might appear to those of us who can work our way through the Flexner Lectures and fill out the intellectual history that the Two Concepts lacked. Popper had the luxury of simply being puzzled by what Berlin was saying and could go on to read what Berlin was offering as an exercise in political philosophy that sought to distinguish two different concepts of liberty. What struck him as questionable in the lecture was its implication that positive liberty and negative liberty were ultimately incommensurable: a conjecture about the implications of a concept, rather than a history. And Popper, of all people, knew what to do with conjectures: try to come up with a refutation.

Popper’s second point, then, can be viewed as an attempt to refute Berlin’s claim that there is an inherent contradiction between positive and negative concepts of liberty by providing a “very simple idea of positive freedom which may be complementary to negative freedom, and which does not need to clash with it.” The example that he provides is — appropriately enough for a friend of Kant — cast in the form of a maxim:

search for truth — sapere aude

Popper prefaces this familiar quotation with the following maxim:

spend one’s own life as well as one can; experimenting, trying to realize in one’s own way, and with full respect to others (and their different valuations) what one values most …

However we understand what Kant was doing with the “motto” he took from Horace, Popper has captured something important about the form in which it is cast: it can only be interpreted as an example of “positive freedom.” In Berlin’s account, the adopting of a maxim (i.e., “search for the truth” or “think for oneself” rather than follow instructions that are given by others) is, and can only be classified as an example of positive, rather than negative, liberty since what is at issue here is a question of who is the source that is determining what I can be or do. Since “sapere aude” is a rule that I give to myself (as opposed to a command from a superior), it counts as an instance of “positive” freedom: it represents an act of self-legislation.

As I have suggested in an earlier post, this way of thinking about the phrase from Horace is not unique to Popper. When read in context, what Horace is advising his young friend Lollius Maximus to do is to adopt a rule for living properly. As my friend Manfred Kuehn has explained in a discussion of Kant’s lectures on anthropology, Kant held that

As free and rational beings, we can and must adopt principles according to which we live, and it is for that reason that character may “be defined also as the determination of the freedom (Willkür) of human beings by lasting and firmly established maxims.” Insofar as character is indeed the characteristic mark of human beings as free and rational beings, living by maxims makes us what we should be. … It is for this reason that he identifies character with our “way of thinking” (Denkungsart), which is opposed to the “way of sensing” (Sinnesart).

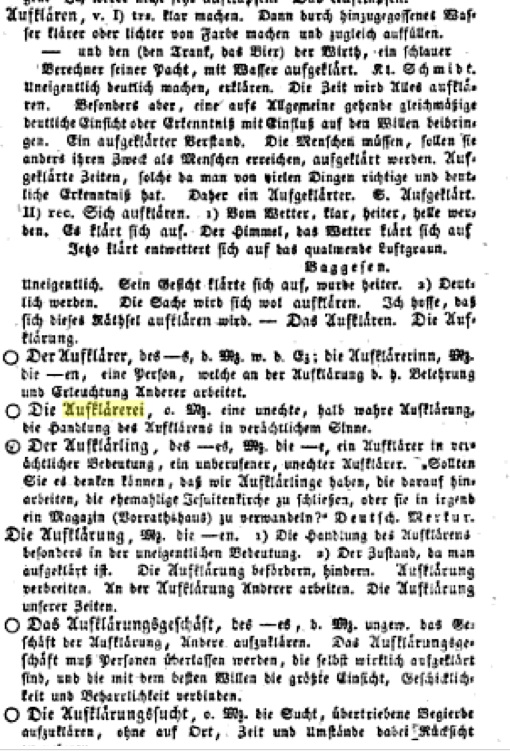

This seems to have been the way in which Horace’s motto was understood by the “Society of the Friends of Truth,” that strange group of Epicurean champions of Leibniz and Wolff who were responsible for coining the medal that graces the right side of this page. They thought that the Horatian imperative could be reconciled with Leibniz’s principle of sufficient reason, hence the rule that they adopted for themselves: “Hold nothing as true, hold nothing as false, so long as you have been convinced of it by no sufficient reason.” Perhaps, a discussion of the difference between their use of Horace’s dictum and Kant’s might introduce some needed complexity into Berlin’s account of the relationship between “the Enlightenment” and the vicissitudes of the concept of positive liberty.

In his letter to Berlin, Popper emphasized the difference between claiming to be in possession of the truth, a claim that looms large in Berlin’s discussion of the dangers that haunt the concept of positive liberty, and the demand to seek the truth through a process of criticism (which Popper saw as the project pursued by Socrates). To quote the crucial passage once again,

No doubt, the idea that anybody is wise, is dangerous and repugnant. But why should sapere aude be interpreted as authoritarian? It is, I feel, anti-authoritarian. When Socrates said, in the Apology, that the search for truth through critical discussion was a way of life (in fact, the best way of life he knew of) — was there anything objectionable in this?

Popper, of course, could find nothing objectionable here. Next week we can see how Berlin responded.

the decision by Anthony Foxx, the mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina, to issue proclamations making May 2 not only a “Day of Prayer” but also a “Day of Reason.” Doocy and Nance had no problems with the former proclamation, but were quite annoyed about the latter.

the decision by Anthony Foxx, the mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina, to issue proclamations making May 2 not only a “Day of Prayer” but also a “Day of Reason.” Doocy and Nance had no problems with the former proclamation, but were quite annoyed about the latter.  Nance, it turns out, is “CEO and President” (there’s a difference?) of something called “Concerned Women of America,” an organization whose “Statement of Faith” goes a long way towards clarifying her reservations about the “Day of Reason”:

Nance, it turns out, is “CEO and President” (there’s a difference?) of something called “Concerned Women of America,” an organization whose “Statement of Faith” goes a long way towards clarifying her reservations about the “Day of Reason”: Fox’s interest in Foxx’s proclamation (stuff like this is enough to make me wonder whether theologians overlooked the most compelling proof for the existence of God: the universe is ruled by an all-powerful intelligence with a wicked sense of humor) might seem momentarily puzzling. Why are these Foxites so worked up over this particular Foxx when there so many other foxes trying to sneak into the great national hen-house? But everything became perfectly clear to me once Mr. Doocy kindly explained that Mayor Foxx is President Obama’s pick to become Secretary of Transportation. Fox News, of course, is interested in everything that President Obama does — indeed, so insatiable is their interest in his doings that they sometimes have to make them up.

Fox’s interest in Foxx’s proclamation (stuff like this is enough to make me wonder whether theologians overlooked the most compelling proof for the existence of God: the universe is ruled by an all-powerful intelligence with a wicked sense of humor) might seem momentarily puzzling. Why are these Foxites so worked up over this particular Foxx when there so many other foxes trying to sneak into the great national hen-house? But everything became perfectly clear to me once Mr. Doocy kindly explained that Mayor Foxx is President Obama’s pick to become Secretary of Transportation. Fox News, of course, is interested in everything that President Obama does — indeed, so insatiable is their interest in his doings that they sometimes have to make them up. What I Saw in America provides some support the last of the four concerns on the Concerned Women of America’s statement of faith:

What I Saw in America provides some support the last of the four concerns on the Concerned Women of America’s statement of faith: