Anthony Pagden’s The Enlightenment and Why It Still Matters (New York: Random House, 2013) is perhaps the most ambitious account of the period published by a major commercial press since Peter Gay’s two-volume survey from the 1960s. Like Gay, Pagden’s aim is to demonstrate the ways in which the Enlightenment made Europeans modern. And, in keeping with the current emphasis on global history, Pagden shows how Europeans became modern by learning what it was that they shared with the rest of the world. As a result, his book devotes considerably more attention than Gay did to the role of modern natural law theories in the development of the Enlightenment and features a fine discussion of the ways in which the attempt to articulate the “science of man” implied by these theories was informed by and tested against the strange peoples and stranger customs that voyagers across the Pacific encountered. And where Gay’s account culminated in an examination of the ways in which the Enlightenment inspired the creation of a republican government on the North American continent, Pagden traces the legacy of the Enlightenment down to the present, arguing that

Anthony Pagden’s The Enlightenment and Why It Still Matters (New York: Random House, 2013) is perhaps the most ambitious account of the period published by a major commercial press since Peter Gay’s two-volume survey from the 1960s. Like Gay, Pagden’s aim is to demonstrate the ways in which the Enlightenment made Europeans modern. And, in keeping with the current emphasis on global history, Pagden shows how Europeans became modern by learning what it was that they shared with the rest of the world. As a result, his book devotes considerably more attention than Gay did to the role of modern natural law theories in the development of the Enlightenment and features a fine discussion of the ways in which the attempt to articulate the “science of man” implied by these theories was informed by and tested against the strange peoples and stranger customs that voyagers across the Pacific encountered. And where Gay’s account culminated in an examination of the ways in which the Enlightenment inspired the creation of a republican government on the North American continent, Pagden traces the legacy of the Enlightenment down to the present, arguing that

although the central Enlightenment belief in a common humanity, the awareness of belonging to some world larger than the community, family, parish, or patria, may still be shakily primitive and incomplete, it is also indubitably a great deal more present in all our lives — whoever “we” might be — than it was even fifty years ago. “Global governance,” “Constitutional Patriotism,” globalization, multiculturalism are not only topics of debate; they are also, in many parts of the world, realities. Cosmopolitanism, expressed as a firm belief in the possibility of a truly international system of laws, has been the animating principle behind both the League of Nations and the United Nations and is the main assumption that underlies the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (413).

We are, he concludes,

inescapably, the heirs of the architects of the Enlightenment ‘science of man.'” For this, then, if for no other reason, the Enlightenment still matters (415).

In the face such an ambitious, informed, and energetic account of the Enlightenment it is perhaps pedantic to note that the book has a minor problem: it misplaces a buttock.1

On the Displaced Buttock

Recounting the sufferings inflicted on the protagonists of Voltaire’s Candide, Pagden observes,

Pangloss, his face half eaten away by syphilis, one buttock cut off, insists that, all appearances to the contrary, this world is nonetheless the ‘best of all possible worlds’ … (114).

He’s is right about Doctor Pangloss’s unflagging optimism and unrelenting syphilis. The lessons in “experimental physics” performed on the “very pretty and very pliable” servant girl by Pangloss’s “sufficient reason” (and let us pause here to ask: has anyone other than Voltaire ever used a philosophical concept as a euphemism for the male member?) result  in his contracting a disease whose genealogy he traces and necessity he demonstrates. But Pagden is mistaken about the fate of Pangloss’s buttocks: at the end of the book, he still has both of them. On the other hand, the Old Lady had one of hers removed (and eaten) by besieged (and starving) Janissaries.

in his contracting a disease whose genealogy he traces and necessity he demonstrates. But Pagden is mistaken about the fate of Pangloss’s buttocks: at the end of the book, he still has both of them. On the other hand, the Old Lady had one of hers removed (and eaten) by besieged (and starving) Janissaries.

Given all that is going on in Candide, it is understandable that Pagden might lose track of a buttock. Catastrophes pile upon catastrophes and, in the larger scheme of things, the Old Lady’s loss, though obviously important to her, seems but a trifle. Things like this happen with appalling frequency in Candide: the slave that Candide and Cacambo meet in Surinam has lost both his left leg and his right hand (such, after all, is the price of sugar) and Cunégonde is gang-raped and disemboweled (though, somehow, not fatally) by Bulgar troops. The sufferings Candide witnesses would be unbearable were it not for the madcap rapidity with which Voltaire recounts them. The book reads like an attempt to imagine how the world might appear to an Angel of History wasted on amphetamines.

Like Candide, Pagden has a lot of ground to cover and, even though he has 400 pages to cover it, he needs to move rather quickly. Things are not made any easier by his having taken on the additional burden of not only providing an account of the Enlightenment, but explaining “why it still matters.” In that regard, Gay had it easier: Knopf gave him two volumes to explain what the Enlightenment was and, having completed that task, he went on to explore why it mattered in The Bridge of Criticism (a book that has remained out of print for far too long: reprint, please!). Gay also had the advantage of writing at a time when the field of eighteenth-century studies was, at least in retrospect, still in its infancy. We know a lot more about the Enlightenment now than we did in 1969, which makes Pagden’s achievement all the more impressive.

Like Candide, Pagden has a lot of ground to cover and, even though he has 400 pages to cover it, he needs to move rather quickly. Things are not made any easier by his having taken on the additional burden of not only providing an account of the Enlightenment, but explaining “why it still matters.” In that regard, Gay had it easier: Knopf gave him two volumes to explain what the Enlightenment was and, having completed that task, he went on to explore why it mattered in The Bridge of Criticism (a book that has remained out of print for far too long: reprint, please!). Gay also had the advantage of writing at a time when the field of eighteenth-century studies was, at least in retrospect, still in its infancy. We know a lot more about the Enlightenment now than we did in 1969, which makes Pagden’s achievement all the more impressive.

Why it Might Not be Such a Good Thing that the Enlightenment Still Matters

Gay began his first volume by (1) noting that the Enlightenment had no shortage of critics, (2) confessing that he’d enjoyed the “polemics” in which he’d been engaged while defending it from its conservative critics, and (3) suggesting that it was time “to move from polemics to synthesis.” Fat chance: when it comes to the Enlightenment, it’s always Ground Hog’s Day and every historian is Bill Murray. There would seem to be a fair number of people (not all of them on the Right) who are quite convinced that the Enlightenment surely does matter. Unfortunately, some of them have only the faintest understanding of what it actually involved.

For example, about a week after The Enlightenment and Why it Still Matters appeared, Penny Nance, the President and CEO of the conservative Christian organization “Concerned Women for America” turned up on the Fox News channel and (as I discussed in an earlier post) informed the Foxites that

the Age of Enlightenment and Reason gave way to moral relativism. And moral relativism is what led us all the way down the dark path to the Holocaust… Dark periods of history is what we arrive at when we leave God out of the equation.

Now, Penny Nance obviously knows considerably less about the Enlightenment than Pagden does, but she seems to be convinced that it still “matters.” She sees herself (or, at the very least, does a good job of making it appear as if she sees herself) as confronting a world that has been laid waste by an Enlightenment that, persistently and relentlessly, keeps on mattering. There is, then, one tiny point on which Nance and Pagden might agree: after some two and a half centuries, the Enlightenment still matters.

And there would seem to have a further point of agreement. Pagden’s aim is to trace how a set of ideas, born in the latter part of the seventeenth century, went on to transform

the most significant, most lasting insights available to the western philosophical tradition in such a way as to make them usable in a world from which God had been finally and irrevocably removed ….

In doing so, the Enlightenment “created the modern world”: it is “impossible to imagine any aspect of contemporary life in the West without it” (408). What Pagden sees the Enlightenment as having achieved is the very same thing that enables Nance to serve as President and CEO of a (tax-exempt?) organization devoted to undoing what the Enlightenment was allegedly trying to do: namely, creating a world in which God is no longer part of “the equation.” Their disagreement lies with whether the Enlightenment’s continuing to matter is a good thing. My reservations have to do with whether this “still mattering” business is a good thing — it might be nice if those of us who work on the Enlightenment could live the sort of quiet life lived by my colleagues in Classics, who study things that, while certainly interesting, are unlikely to turn up on Fox News.

While Nance is convinced that the Enlightenment was bent on removing God from “the equation,” there has been a fair amount of recent scholarship stressing the need to get Him back into the Enlightenment: consider, for example, the fine work that has been done by David Sorkin, Johathan Sheehan, Peter Harrison, Michael Printy, and others.2 Pagden is too good a historian to be unaware of the persistence of various forms of religious belief — many of them interesting, most of them utterly irrelevant for the present 3— during the Enlightenment or of the significant role of clergy, especially in Protestant Europe, in the circulation of enlightened ideas (it is, for example, perhaps significant that clergymen were well represented in the Mittwochsgesellschaft, the Berlin society of “Friends of Enlightenment” responsible for publishing the Berlinische Monatsschrift, an “enlightened” journal that periodically included sermons in its offerings). But The Enlightenment and Why it Still Matters tends to marginalize such matters.

Pagden notes that Hobbes insisted he was not an atheist, but then goes on to assure the reader that he “most probably was” (97).4 He grants that were few thinkers “who were  prepared to contemplate Smith’s ‘fatherless world’ entirely without flinching” (125), but he doesn’t have much to say about the flinchers: the Enlightenment whose history he is tracing does appear to involve them. In a discussion of Granville Sharp, the great opponent of the slave trade, he notes that “For all his devout Christianity, Sharp was as sincere a believer in equal rights for men and women as he was in equality between the races …” (228), thus implying that religious faith was an impediment to a belief in human rights. Likewise, we are told that “the Spanish Benedictine Benito Jerónimo Feijoo, who despite his profession and undoubted faith was in this respects (sic), as in many others, one of the most “enlightened” minds of the early eighteenth century … (265),” which suggests that Pagden assumes that, during the eighteenth century, faith and enlightenment were necessarily antithetical (and also suggests that Random House really needs to hire a few more proofreaders). Not the least of the problems with people like Penny Nance is that they have the capacity to make it seem as if Jonathan Israel’s “Radical Enlightenment” was the only Enlightenment that mattered.

prepared to contemplate Smith’s ‘fatherless world’ entirely without flinching” (125), but he doesn’t have much to say about the flinchers: the Enlightenment whose history he is tracing does appear to involve them. In a discussion of Granville Sharp, the great opponent of the slave trade, he notes that “For all his devout Christianity, Sharp was as sincere a believer in equal rights for men and women as he was in equality between the races …” (228), thus implying that religious faith was an impediment to a belief in human rights. Likewise, we are told that “the Spanish Benedictine Benito Jerónimo Feijoo, who despite his profession and undoubted faith was in this respects (sic), as in many others, one of the most “enlightened” minds of the early eighteenth century … (265),” which suggests that Pagden assumes that, during the eighteenth century, faith and enlightenment were necessarily antithetical (and also suggests that Random House really needs to hire a few more proofreaders). Not the least of the problems with people like Penny Nance is that they have the capacity to make it seem as if Jonathan Israel’s “Radical Enlightenment” was the only Enlightenment that mattered.

Pagden contra MacIntyre

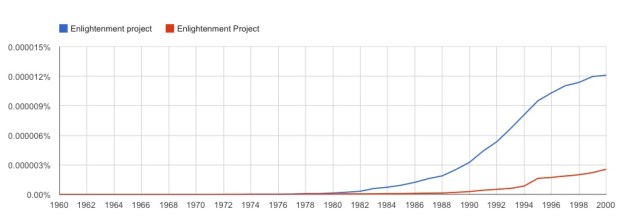

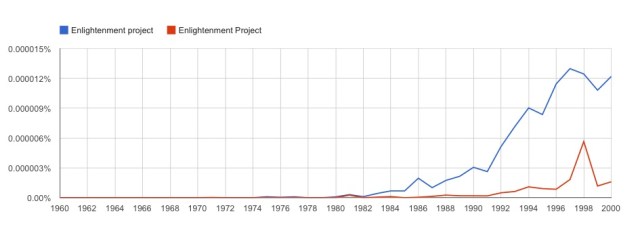

The prevalence of opinions of the sort that Nance was peddling on Fox helps to explain  why Pagden found it necessary to begin his book with a brief discussion of critics of “the Enlightenment project” (16-20) and end it with a chapter on “Enlightenment and its Enemies” (373-415). Fortunately, he has abler critics than Nance with whom to argue: Alasdair MacIntyre plays a leading role in both discussions. Unfortunately, Pagden tends to minimize the differences between MacIntyre (who has some important points to make) and Jean-François Lyotard (who, as far as I can tell, doesn’t).

why Pagden found it necessary to begin his book with a brief discussion of critics of “the Enlightenment project” (16-20) and end it with a chapter on “Enlightenment and its Enemies” (373-415). Fortunately, he has abler critics than Nance with whom to argue: Alasdair MacIntyre plays a leading role in both discussions. Unfortunately, Pagden tends to minimize the differences between MacIntyre (who has some important points to make) and Jean-François Lyotard (who, as far as I can tell, doesn’t).

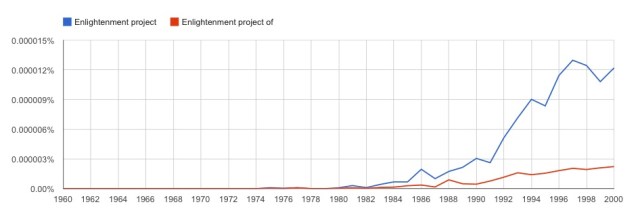

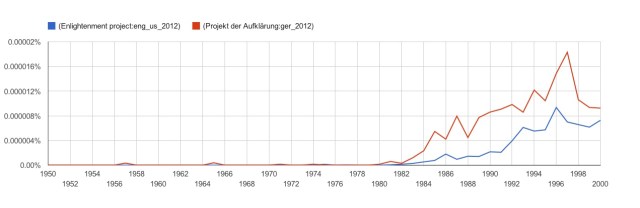

Pagden credits MacIntyre with having coined the “much-quoted and much abused phrase ‘the Enlightenment project'” (16) — as I’ve suggested in an earlier post, it’s not clear that this is true — and MacIntyre’s “extreme” and “historically eccentric” account of the Enlightenment (397) serves as the perfect foil for Pagden’s closing defense of his particular version of the Enlightenment. For Pagden, the great achievement of the Enlightenment was that it “made it possible for us to think … beyond the narrow worlds into which we are born, to think globally” (408). MacIntyre’s characterization of human beings as homo fabulans — creatures who tell stories — and his argument that our moral sensibilities are “essentially narrative ones” make him seem the very model of the modern counter-Enlightener.

Because the “moral sensibilities” of MacIntyre’s homo fabulans are “essentially narrative ones,”

the stories he tells are not about “humanity” or the cosmos, because although both may, in some sense, be said to have stories, none of them are very pertinent or compelling ones (398).

In other words, if MacIntyre is right, then stories we tell will deal with matters that are local, rather than global (398). Locked into these local narratives, we will be incapable of cultivating those cosmopolitan perspectives that allow us to understand other societies.

For in a world conceived in the way MacIntyre, and many other communitarians, conceive it, justice cannot possibly be “global,” because justice, too, can only ever be a matter of agreement among the members of the tribe, community, nation, and so on to which it applies. MacIntyre’s conception of humans as storytelling animals, and of human social lives as structured by narratives, is also the source of Jean-Francois Lyotard’s critique of what he calls the “cosmopolitical” (400).

With this peculiar coupling of MacIntyre and Lyotard, I fear that The Enlightenment and Why it Still Matters jumps the shark. In rapid succession we are told that the line of argument that Lyotard takes over from MacIntyre means that

When confronted with child marriage, slavery, castration, all I can do is stand aside and say, “I have no language with which I can describe, let alone judge, such behavior.” (401)

Which means that:

The true communitarian cannot, therefore, adequately explain how slavery, forced marriages, bearbaiting, or public executions ever came to be considered distasteful (402).

It is possible that Lyotard believes this sort of stuff, but MacIntyre doesn’t.

At the risk of picking nits, it is worth remembering that, though MacIntyre bears some (though, as I’ve suggested, not all) of the credit or blame for popularizing the term “Enlightenment project,” his concern in After Virtue was with one rather specific Enlightenment project. Chapter 5 of After Virtue is entitled”Why the Enlightenment Project of Justifying Morality Had to Fail.” Every subsequent right header in the chapter carries the title “Why the Enlightenment Project Had to Fail.” Nitpickers like me think this is a difference worth emphasizing. After Virtue is not suggesting that the Enlightenment somehow eradicated our ability to praise or to damn various practices. From the very start, MacIntyre makes it clear that we continue to employ moral terms. But we are, he insists, incapable of justifying the ways in which we use these terms. He argues that the alleged failure of the Enlightenment to provide a convincing justification of the moral distinctions that we continue to employ explains why our use of moral terms resembles the description of moral evaluation that emotivists provide. In hopes of providing a better account of how we might justify our use of value terms, he proposes that we go back to Aristotle and see how moral philosophy was once situated in a more ambitious account of virtues and practices.

There may be much that is problematic here and MacIntyre has been quite forthright in responding to his critics and in attempting to elaborate, in a variety of ways, the implications of his critique of the various projects that defined the Enlightenment.5 There is much here that friends of the Enlightenment may want to question (including, perhaps, the idea that “the Enlightenment” is the sort of thing that is amenable to “justification”). But nothing in what MacIntyre argues implies that he is incapable of explaining how slavery came to be seen as “distasteful,” much less that our “local narratives” are somehow unable to talk about “global” concerns. To conclude that, one would have to think that our languages are prison houses or windowless monads. Perhaps Jean-François Lyotard thinks they are. MacIntyre doesn’t.

Back to the Buttock

In the introduction to his translation of Candide, David Wootton offers a brilliant discussion of the significance of the Old Lady in Voltaire’s tale.6 He argues that it is the story of her sufferings, which she recounts as Candide and his friends begin their voyage to the New World, that begins to free Candide from Pangloss’s incessant optimism and  tempers his beloved Cunégonde’s despair. As the characters begin to tell their stories, Voltaire’s sendup of “every tired convention of contemporary romances” is transformed into “a book about the educative and therapeutic power of storytelling.” The lesson of Candide, Wootton argues, is that most of the ways that we “talk about metaphysics, even about politics, is … worthless.” Pangloss exemplifies an enlightenment that, having managed to explain everything, winds up teaching us nothing. But in writing Candide, Voltaire discovered another way to talk about politics: he would learn “to tell stories of personal disaster,” stories “which inspired sympathy and indignation.”

tempers his beloved Cunégonde’s despair. As the characters begin to tell their stories, Voltaire’s sendup of “every tired convention of contemporary romances” is transformed into “a book about the educative and therapeutic power of storytelling.” The lesson of Candide, Wootton argues, is that most of the ways that we “talk about metaphysics, even about politics, is … worthless.” Pangloss exemplifies an enlightenment that, having managed to explain everything, winds up teaching us nothing. But in writing Candide, Voltaire discovered another way to talk about politics: he would learn “to tell stories of personal disaster,” stories “which inspired sympathy and indignation.”

Several years ago, I persuaded those who administer my university’s Core Curriculum to include Candide in the section of the humanities sequence that (briefly) considers the Enlightenment. After the book was added, a somewhat puzzled colleague who teaches in the Core asked me, “Is Candide an “Enlightenment” text?” Sensing that I was in for a strange conversation, I responded “Yes.” He looked puzzled and then muttered, “It sure doesn’t seem like one.” All I could say was, “Well, I suppose a lot depends on what you mean by “enlightenment.”7

The sort of enlightenment in which Voltaire was engaged is rather different from the Enlightenment that Pagden presents. Pagden maintains that the cosmopolitan values that “most educated people, at least in the West, broadly accept” (407) are the result of a search for “a scientifically grounded set of premises for a universal law” on which “all reasonable, rational human beings could agree, no matter what their religious beliefs or national allegiances” (340). In this story, Samuel Pufendorf, Christian Wolff, Emer de Vattel, and Immanuel Kant take the lead. Voltaire figures in it as well, but mostly for his battles against religious dogma than for his 1770 tract On Perpetual Peace, which — in contrast to Kant’s more famous treatise on the topic — was concerned with religious toleration rather than cosmopolitan rights.

For Pagden’s critique of MacIntyre to work it is not enough to trace the ways in which the ideas of the various natural law theorists who loom so large in his account came to be appropriated by “an international intellectual elite, much like the kind constituted by the higher echelons of the academic world today” (323).8 MacIntyre is well aware that cosmopolitan elites — both in the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries — make use of a vocabulary in which “cosmopolitan rights” play a prominent role. His concern with such expressions is philosophical, not historical. His question is not whether these concepts have won out over their rivals but, instead, whether they deserved to win: that is, whether the heirs of Pufendorf, Wolff, Vattel, and Kant have been any more successful in providing compelling ways of justifying these rights than their eighteenth-century predecessors (who, it should be noted, tried to do this a number of conflicting ways).

My interest, on the other hand, is more historical than philosophical. It’s not at all clear to me that approaches like the one that Voltaire was taking in Candide (a phenomenally successful little book) were of less importance in making the modern world less brutal than it might have been than the approach taken by the spinners of those grand cosmopolitan narratives. After all, Pangloss was nothing if not cosmopolitan: he was a disciple of Leibniz and Wolff.

Voltaire, as Wootton stresses, tended to focus on particular abuses — for example, his struggle to clear the name of the persecuted Huguenot Jean Calas and his long campaign against judicial torture. When compared to an “Enlightenment project” that marches from Pufendorf through Kant and onward to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Union, this obsession with specific outrages may, like the Old Lady’s concern for her missing buttock, seem rather parochial. But what MacIntyre and some of the other alleged “enemies of the Enlightenment” are suggesting is that explaining why various evils are, indeed, evil by deducing them from “a scientifically grounded set” of cosmopolitan principles may not be the only — or even the most effective — way of coming to see them as wrong.

Let’s close with this: In the Second Treatise, John Locke marshaled the standard natural law arguments against slavery, yet continued to serve the slave-holding  proprietors of the Colony of Carolina.9 And, as Pagden is well aware, the author of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789) — though not particularly well-versed in natural law theories (and, even more inconveniently, an enthusiastic Methodist) — proved to be a uniquely effective opponent of slave trade. Friends of the Enlightenment are lucky to have enemies like MacIntyre: they help us to understand the diversity of enlightenments that have mattered.

proprietors of the Colony of Carolina.9 And, as Pagden is well aware, the author of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789) — though not particularly well-versed in natural law theories (and, even more inconveniently, an enthusiastic Methodist) — proved to be a uniquely effective opponent of slave trade. Friends of the Enlightenment are lucky to have enemies like MacIntyre: they help us to understand the diversity of enlightenments that have mattered.

On the other hand, I could easily do without Penny Nance.

- There is also an odd collision on p. 376 between the names of Johann Heinrich Tieftrunk (Kant’s disciple) and Arthur Hirsh (who translated Tieftrunk’s essay for my What is Enlightenment? collection) that results in the creation of a pupil of Kant’s named “Johann Heinrich Hirsch.” ↩

- David Sorkin. The Religious Enlightenment : Protestants, Jews, and Catholics from London to Vienna. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008, Jonathan Sheehan. The Enlightenment Bible : Translation, Scholarship, Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005, Peter Harrison. “Religion” and the Religions in the English Enlightenment. Cambridge England ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990, and Michael Printy, Enlightenment and the Creation of German Catholicism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. ↩

- Time for my favorite story about Deists, which I posted to the 18th Century Discussion list back in August 2001 (i.e., a month before the World as We Know It was — temporarily? — suspended):One of the more peculiar road-side attractions in New England is the Traveler Book Restaurant, just over the Connecticut line from the Mass Turnpike in Union, Connecticut. The first floor of the restaurant looks like it might have escaped from Twin Peaks (notty pine on the walls and lots of good pies in the kitchen). Downstairs in the basement there’s a used book store, usually staffed by charming older women, who carefully hand-total every order and keep watch on the inventory. …The book theme is carried over into the restaurant in two ways: 1) everyone who eats there gets to pick a free book from some special stacks in the entryway (I scooped up a copy of The Leopard) and 2) the walls are plastered with little shrines to authors (Steven King, Jackie Collins, Judy Blum, etc.) that, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, the restaurant has decided to honor with a picture, a bibliographical note, a bibliography, and — usually — a letter to the restaurant from the author.After a long drive from the Philadelphia area, I found myself seated underneath Doctor Seuss while, on the opposite side of the table, my son was under the shrine to John Toland. “Who’s John Toland?” he asked, and I explained that there were two of them: the great Deist and the twentieth-century historian of Germany. From the biography and the letter, it was clear that it was the latter who was being honored, but my son noted a problem in the bibliography: the historian Toland was being credited, not only with a biography of Hitler and various books on Germany, but with “Christianity Not Mysterious,” “Letters to Serena,” “Pantheisticon,” and so forth. So, at the end of the meal, as the pies were being cleared away and the waitress asked how everything was, I explained that while the meal was fine, there were problems with John Toland’s bibliography. She listened attentively as I explained their confusion of the two Tolands (probably more attentively than I deserved — driving too much for too long can make one rave a bit) and then she commented, “It’s amazing no one caught this before.” This allowed me to deliver a line that, as it escaped my mouth, struck me as something that one could spend a life-time waiting to get the chance to say: “Well, I guess you don’t get many Deists in these parts.” ↩

- For a good attempt to sort out Hobbes’ religious beliefs, see Richard Tuck, “The Christian Atheism of Thomas Hobbes.” In Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment, edited by Michael Hunter and David Wootton. Oxford University Press, 1992. ↩

- The attempt that is most relevant for my own work is his 1995 essay, “Some Enlightenment Projects Reconsidered,” now available his Selected Essays, Volume 2, 172-185. in ↩

- Voltaire, Candide and Related Texts translated, with an Introduction, by David Wootton (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2000) xx-xxiii. ↩

- The nice thing about talking with colleagues is that I didn’t have to worry about whether to capitalize “Enlightenment”; I hear that Jacques Derrida wrote something about this. ↩

- I’ve pondered whether it is fair to quote this passage, which I suspect is something that, viewed out of context, comes off as a bit smug. For reasons I can’t entirely explain, the sort of cosmopolitanism Pagden winds up defending strikes me as somewhat off-putting. Perhaps I’ve been corrupted by MacIntyre. Or maybe it’s that I always fly in coach. ↩

- David Armitage, “John Locke, Carolina, and the ‘Two Treatises of Government’.” Political Theory 32:5 (2004): 602–627. ↩